Lecture Notes-1

Motives and Professional Ethics

A definition of engineering appropriate to our discussion is, a positive tone of Sixth Commendment

” Thou shalt not Kill”

into

” you must safe guard the society”

Causal and Legal ResponsibilityCausal Responsibility

Being the cause of an event is not always the same as being responsible for the event.

Children playing with matches

Child shooting another with parent’s gun

Pilot with reversed controls flying into a mountainLegal Responsibility

One might be found legally responsible for an event and still be morally pure.

Chip flies off hammer, blinding user

- product problem – bad steel

- design problem – no bevel

- improperly used

- used beyond expected life

Step ladder manufacturer

- inherently dangerous product?

- pass cost of liability on to consumer

Contract law can create the converse; no legal responsibility, but clear moral responsibility.

The fine print of a contract releases the designer or engineer from liability.

The fine print of a contract assigns the designer’s or engineer’s liability to the client.

One reason so many persons are named in law suits is that a contract can not protect a person from the consequences of actions in all cases:

Negligence

Willful wrong doing

Causal and legal responsibility have been shown to be different from moral responsibility.

To say an engineer “is responsible” (acts responsibly) ascribes to that person a conscientious concern for the moral ideals and aims of engineering.

A responsible engineer is motivated (in part) by respect for safety and the autonomy of the public and the client (employer).

Other motivations exist:

Self-interest (but not selfishness)

Professional excitement

Pursuit of excellence

To the extent that these nonmoral motives reinforce moral behavior and responsibility, they are positive. Any of these motives can lead to dilemmas for the engineer if pursuing them conflicts with moral responsibility. But the dilemmas are not moral; the engineer presumable knows what is morally required.

Personal Integrity an Virtues

Professional responsibility can not be divorced from personal integrity “I was just following orders” is no defense because there is a direct link between professional behavior and personal integrity.

Virtues provide a bridge between private and professional lives.

Virtues are general patterns of behavior, emotion, and attitudes that permeate all areas of life.

Moral integrity can be defined as inner unity on the basis of moral commitments.

Moral integrity is maintained when virtues are manifested across the bounds of both personal and professional life.

An engineer is not simply a part in a machine. Machine parts can’t think; being human carries the special obligation to think.

Similar reasoning explains why statements like:

“If I don’t do it, someone else will” or,

“I might as well do it, everyone else does” Are insupportable.

Moral behavior does not depend on what others do (or don’t do). Persons who claim these excuses are failing to take responsibility for their actions.

As Engineers we’ve to balance our self-interest with our moral obligation to safe guard the society.

In this context we don’t want to be preached about what is right or wrong, rather we would like to take autonomous decision after thorough analysis.

Self-Interest and Ethical Egoism

Moral behavior can be recognized as behavior that is good for the individual in the long run.

The sole duty of each of us is to maximize our own good.

Moral values are reduced to concern for oneself (prudence) – but in the long term.

Paradox of Happiness

To seek happiness without regard for the happiness of others leads, in the long run, to one’s own unhappiness.

The Pursuit of Self-Interest

Everyone benefits if all pursue their own self-interest

Society benefits most when

1. individuals pursue their own self-interest, and,

2. corporations (as expressions of the will of many individuals) pursue maximum profits in a free market environment. – Adam Smith

Ethical Egoism does provide guidance for behavior, but it denies the more global notion of moral behavior.

Laws and Ethical Conventionalism

The laws, customs and conventions of a society define morality.

Proponents argue that:

1. Laws are objective; easy to use as guides for behavior.

But, laws can be analyzed using morality as a point of view; apartheid is wrong, morally wrong. So moral values seem to justify the subjective nature of law.

2. Ethical Conventionalism leads to tolerance toward others by viewing their conduct as morally correct; right for them though wrong for us.

But, few would argue that Nazi Germany’s laws regarding Jews was in any way morally correct.

Ethical Conventionalism seems to suggest that believing something to be correct makes it so.

- Flat earth

-Slaves as subhuman

Religion and Divine Command Ethics

To say an action is right means it is commanded by God; a wrong action is forbidden by God; without God there is no morality.

But, Socrates asked, in effect, “Why does God make certain commands? Are the commands of God based on whim? Surely not, God is (morally) good.

Divine Command Ethics seems to have things backwards- instead of commands of God creating morality, moral reasons provide the foundation for the commands of God.

This discussion does not rely on questions of the existence or supremacy of God. Nor does it deny the importance or the purpose of religion, which is, in part, to motivate right (moral) action.

Minimal Conception of Morality

Morality concerns reasons for the desirability of certain kinds of actions and the undesirability of others.

What are moral reasons?

Reasons which require us to respect others, to care for their well-being in addition to our own.

Reasons which place limits on the legitimate pursuit of happiness.

Reasons that can be used to analyze laws, customs, and conventions.

Moral conduct is based on concern for others, it is not reducible to self-interest, law or religion.

But, can we be more precise about what makes some actions morally correct, and others not? We are getting there…

Four Types of Moral TheoriesConsider the Agnew kickback scheme:

As County Executive for Baltimore County from 1962-1966 had the authority to award contracts for public works projects to engineering firms. In exercising that authority, he functioned at the top of a lucrative kickback scheme.

Lester Matz and John Childs were two of many engineers who participated in the scheme. Their consulting firm was given special consideration as long as they made secret payments to Agnew of 5% of fees from clients. Even though their firm was doing well, they entered into the arrangement to expand their business. They felt that in the past they had been denied contracts from the county because they lacked of political connections.

It is easy to see that such behavior is unethical. But why is it unethical? What moral principles were violated?

Four types of theories are currently being debated; they differ mainly in what principles they consider most important.

Ethical Theories

Theory Proponents Basic Concept

Utilitarianism Mill/Brandt Most good for most people

Duty Ethics Kant/Rawls Duties and responsibilities

Rights Ethics Locke/ Melden Human rights

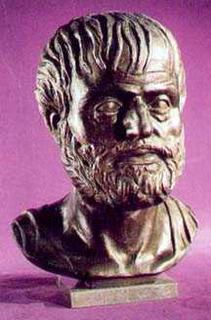

Virtue Ethics Aristotle/ MacIntyre Virtues and vices

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is the view that we ought to produce the most good for the most people, giving equal consideration to everyone affected.

Mill: Act-Utilitarianism and Happiness

Act-utilitarianism suggests we should focus on individual actions rather than general rules. An action is right (moral) if it is likely to produce the most good for the most people involved in a particular situation. Rules are useful as guides because experience has shown that following them often leads to good results. Rules like

Keep your promises

Don’t deceive

Don’t bribe

should be broken whenever doing so will optimize good results.

What does it mean to “maximize goodness”? Mills believed that happiness is the only intrinsic good. All other good things are “instrumental goods” in that they provide the means for happiness.

The notions of “goodness” and “happiness” and causual affects of acts is the principal problem with act-utilitarianism.

Brandt: Rule-Utilitarianism

Moral rules are primary (as opposed to right action). We ought to act on those rules which, if generally followed, would produce the most good for the most people. Individual actions are right (moral) when they conform to those rules.

Rules should be considered in sets that Brandt calls “moral codes”. A moral code is justified when it consists of a set of rules which, if adopted and followed, would produce the most overall good. Such a code is said to be optimal. Code sets may be very general, or highly specific (like engineering codes of ethics).

Actions can be tested by casting the acts into rules:

Rule: Engage in secret payoffs when necessary for profitable business ventures.

Matz and Childs

Rule: Break the law when you can get away with it.

Agnew

Clearly, application of these rules does not produce optimal good.

Most utilitarian have abandoned act-utilitarianism because it seems to open loopholes that are difficult to judge.

Duty Ethics

Right actions are those required by a list of duties such as:

Be honest

Keep your promises

Don’t inflict suffering on others

Be fair

Make reparation when you have been unfair

Duties to ourselves:

Improve one’s own intelligence and character

Develop one’s talents

Don’t commit suicide

Kant: Duties and Respect for Persons

Duties, rather than consequences, are fundamental. Why are the above duties? According to Kant, because they meet three conditions:

each expresses respect for persons

each is an unqualified command for autonomous moral agents (categorical imperatives)

each is a universal principle.

Respect for persons

To respect persons is to fulfill our duties to them. To respect oneself is to fulfill our duties to ourselves.

Categorical imperatives

Moral imperatives have no conditions attached; hypothetical imperatives do.

If you want to be happy, enrich your life with friends

Your money or your life

are hypothetical imperatives. Command is based on some condition.

Universality

Categorical imperatives are binding on us only if they apply to everyone.

Prima Facie Duties

Kant believed principles of duty were absolute. He did not speak to the possibility that absolute rules can lead to conflict, thereby creating moral dilemmas. Modern ethicists address this issue by defining “prima facia” duties, i.e., principles of duties that have exceptions.

“Do not deceive”

can be ignored if it comes in conflict with a higher principle, e.g.,

“Protect innocent life”.

Rawls: Principles of Duty Ethics

John Rawls tries to formulate general principles that can be ranked in order of importance without having to rely on intuitive judgments.

Valid principles of duty are those that would be voluntarily agreed upon by all rational persons in a “contracting” situation.

A rational person

1. Lacks all specific knowledge of himself.

2. Has general knowledge of human societies and science.

3. Has a rational concern for his long-term interests.

4. Seeks to negotiate a principles all will voluntarily follow.

All rational people will (according to Rawls) agree to abide by two basic principles, namely,

1. Each person is entitled to the most extensive amount of freedom compatible with an equal amount for others.

2. Differences in social power and economic benefits are justified only when they are likely to benefit everyone, including members of the most disadvantaged group.

(HUMAN) RIGHTS THEORY

Locke and Liberty Rights

Human rights ethics differs from duty ethics in believing that human rights form the highest principle; we have duties because others have rights. For example, individuals do not have a right to life because others have a duty not to kill them, but rather, the duty to protect life (not kill) arises from the right to life.

Locke argued that to be a person entails having rights- human rights- to life, liberty and property generated by one’s labor. Locke’s view of rights are now called liberty (or negative) rights. Such rights place duties on other people not to interfere with one’s life. Locke’s theories had a strong influence on the founding fathers and are reflected today in libertarian ideology.

Melden: Welfare Rights

In sharp contrast to the highly individualistic notion of human rights espoused by Locke, Melden proposes that such rights arise out of interactions of individuals in a community. He argues that having moral rights presupposes the capacity to show concern for others and to be accountable in a moral community.

In Melden’s view, rights are positive: they place an obligation on individuals in a community to provide all with benefits needed to lead a minimally decent human life. Melden’s approach defines welfare rights.

Responsibility and Virtue Ethics

Preoccupation with procedures useful in confronting and evaluating moral dilemmas should not lead us to neglect the heart and spirit of true professionalism; the morals and ideals to which a profession is dedicated, and the moral character of its practitioners. Moral character, as defined by vices and virtues, has as much to do with motives, attitudes, aspirations, and ideals as it does with right and wrong conduct.

Aristotle: Virtue and The Golden Mean

Virtues are acquired habits that enable us to engage effectively in rational activities – activities that define us as human beings.

Intellectual Virtues – foresight, efficiency, creativity, mental discipline, perseverance, etc.

Moral virtues – courage, truthfulness, generosity, friendliness, etc.

The Golden Mean suggests that moral virtues occupy the middle ground between two extremes:

foolhardiness – courage – cowardice

tactlessness – truthfulness – secretiveness

wastefulness – generosity – miserliness

Moral virtues allow us to pursue a variety of social goods within a community.

MacIntyre: Virtues and Practices

In order to apply virtue ethics to professional ethics, MacIntyre introduces the idea of practices-cooperative activities aimed toward achieving social goods that could not otherwise be achieved. The goods are said to be internal goods because they are the results of the workings of the practice. External goods, fame, fortune, prestige, etc., can be gained in many ways; internal goods are the result of practice.

The primary internal goods of medicine are good health and respect for patient’s autonomy; the primary internal good of the law is social justice.

What is the primary internal good of engineering? The primary internal good of engineering is the creation of useful and safe products while respecting the autonomy of clients and the public. A responsible engineer is motivated (in part) by the safety and autonomy of the public.

No comments:

Post a Comment